Kawésqar

Los Kawéshqar o Alacalufes

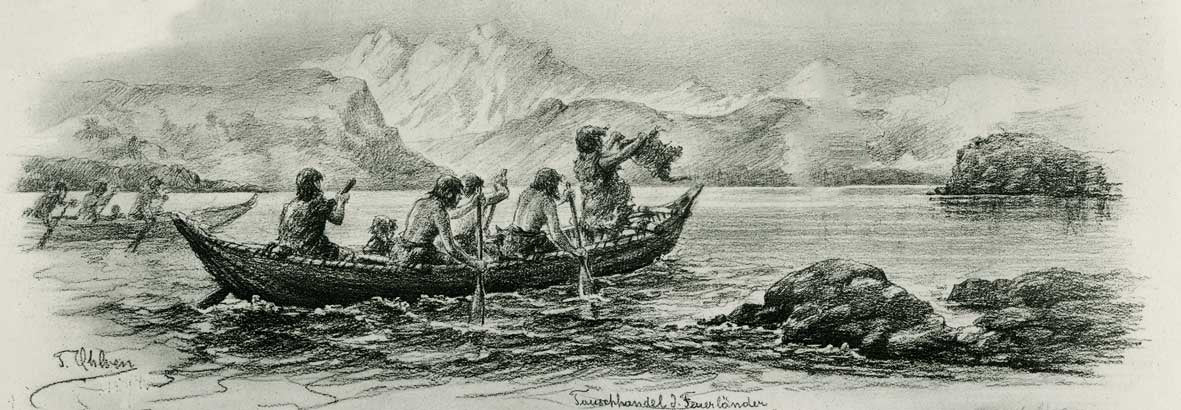

An ancestral inhabitant of the Patagonian channels, they forged a deep connection with the cold waters of southern Chile. With mastery of canoes and intimate knowledge of the tides, they sustainably harvested shellfish and seaweed, shaping both their culture and cuisine. Their oral stories convey wisdom about currents, the climate, and the stars—testaments to an unbreakable bond with the sea. Today, their living legacy embodies respect for the marine ecosystem, inspiring us to cherish the ocean’s bounty.

At Patagonia Seafoods, our relationship with the ocean is deeply inspired by the ancestral connection the Kawésqar people have with the southern Chilean seas. Just as they skillfully navigated the Patagonian channels with respect and deep knowledge, we honor that legacy through responsible artisanal fishing that values the purity of the environment and the exceptional quality of every product. With that same connection to the sea, we bring the best of our coast to the U.S. and Puerto Rico — keeping a tradition alive that bridges past and present in every shipment.

Connection With The Waters

The Kawésqar people have lived for thousands of years among the fjords, islands, and channels of Chilean Patagonia, in one of the most remote and pristine marine ecosystems on the planet. For them, the sea was not just a source of food, but a sacred and central part of life — a place of learning, travel, and deep spiritual meaning. From their hand-carved canoes, they read the winds, tides, and stars, mastering nature’s rhythms to navigate safely and fish with respect. Shellfish, sea lions, and seaweed sustained their communities, while their oral traditions preserved vast knowledge of the sea and coastline. Today, the spirit of the Kawésqar people continues to inspire respect for the ocean and its delicate balance.

Body Painting

In Kawésqar culture, body painting was linked to ritual practices, such as funerary rites and protection during journeys through the channels. When a harmful spirit was feared—like after spotting a leopard seal near a camp—women and children would take refuge in the At, and children’s faces were painted while men hunted the animal. The paintings featured lines and dots in white, black, and red. Red pigment held special value and was considered a wal (a “thing of value”) due to its rarity.